Behind every great band there stands a figure who was essential in successfully getting that group seen and heard: the artist manager.

Though many managers follow the ‘best seen and not heard’ mantra, it’s not always the golden rule when it comes to getting the unruliest of bands on stage, on time, or even in the same tour vehicle together. The rock star pantheon is littered with managers who took a more unconventional approach and managed to get their artist exactly what they wanted – on their own terms.

Some of the biggest names in music, like Elvis Presley, The Sex Pistols, and Oasis, had equally powerful forces pushing them into the historical positions they are in today. But what exactly does an artist manager do?

“Everything? A lot. Nothing. All of those,” comes the response from Neal Hunt. Currently managing rising Sydney stars Sticky Fingers after curating the career of The Beautiful Girls for nearly a decade, Hunt is not only an experienced hand in the Australian music scene, but also a teacher at the Australian Institute of Music (AIM) where students glean valued expertise from Hunt’s industry experience.

Speaking about the unique relationship between the artist and the manager, Mr. Hunt offers some valuable advice about cultivating positive careers in the industry. To prove the point, we’ve paired his top-tier management advice with a selection of five of music’s most infamous managers to illustrate this rather unsung, but critically important role in the music industry that can be about so much more than setting up tour paths, release lists, booking shows, and organising logistics.

Colonel Tom Parker

The high-profile manager of ‘The King’, the Colonel was actually born in the Netherlands as Andreas Cornelius van Kuijk, which explains chiefly why Elvis Presley never toured outside the US: Colonel Tom Parker was an illegal immigrant and would be refused entry if he left the country. Shaping the career of his world-famous blockbuster client, the Colonel insisted on a 50% commission on all of Elvis’ dealings, ultimately leading many to believe he did more harm than good for the King.

“The term good management is probably a bit subjective, or need dependent,” Hunt explains. “The Colonel’s management of Elvis most likely wouldn’t have fitted with Soundgarden, and may not have done so well with the Beatles.” Still, without Parker’s ruthless managerial approach, Presley may not be the deathless music icon he has become.

Love The Beatles?

Get the latest The Beatles news, features, updates and giveaways straight to your inbox Learn more

Peter Grant

“The relationship between the artist and manager flows out from the goals or the needs of the artist at the time – and includes the management (or perpetuation) of the issues and streams of income that they need to have done and those that they are either not happy to do, or don’t have time to do, themselves,” Hunt says. Take for instance Led Zeppelin’s hulking 6-foot manager, Peter Grant, who would do anything and everything to get the British rock band what they needed.

With his utter determination in Zep, combined with his tendency to physically intimidate those in his way thanks to his former career as a bouncer and wrestler, Grant was the bad-ass personification of a manager who would do what others ‘weren’t happy to do’, and one of the first managers to push for artists to get a majority cut of profits from concert earnings and securing Led Zeppelin’s landmark five-album Atlantic record deal.

Tony Wilson

“Finding a manager who is good across all the duties/disciplines is going to be difficult. Some managers come from an accounting background and are good at that side of mgmt and others are more driven by artist development or a creative development level,” says Hunt. “I guess the dominant commonality can be found in determining and achieving artist goals.”

That idea may be no more clearer than in television presenter-turned-Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, who famously put Manchester on the map by managing influential acts like A Certain Ratio and The Durutti Column. Wilson also signed and launched the careers of Factory perennials like Joy Division and Happy Mondays. Finances were never in Wilson’s management ‘style’.

In 1983 with Factory already struggling financially, Wilson OK’d the cover for New Order’s “Blue Monday”. The inventive sleeve, designed as a floppy disk, cost so much to make that Factory still lost money with every sale. To make matters worse, it became the fastest selling 12 inch of all-time. Just one example of many bizarre tales, many which are chronicled (with some fictitious fervour) in 24 Hour Party People.

Glenn Wheatley

“I think a good manager will be looking to expand. So working to create opportunities in territories for the artist,” explains Hunt. “Pretty much wherever there’s a stream of income there’s a manager somewhere nearby.”

Glenn Wheatley certainly fits that bill; though he was a member of Australian rockers The Masters Apprentices, Wheatley is best known as the manager to John ‘The Voice’ Farnham.

Overseeing his singer’s career and impact into the US (and the countless farewell tours over the years), Wheatley began his association with no formal agreement with Farnham other than a gentleman’s handshake. He also mentored Australian rock band the Little River Band and, much later, Delta Goodrem, and was instrumental in launching what is now known as Triple M.

But it hasn’t all been roses. The financial collapse in the 90s nearly took Wheatley with it, and his nightclub The Ivy in particular was a financial burden. The successful promoter and manager later became embroiled in a tax evasion scandal in 2007, facing 16 years jail.

In the end Wheatley only served 15 months after he was found guilty of channelling more than $650,000 through tax fraud schemes, and is back promoting John Farnham for yet another comeback tour following the purchase of a number of North Queensland radio stations. Now that’s multitasking.

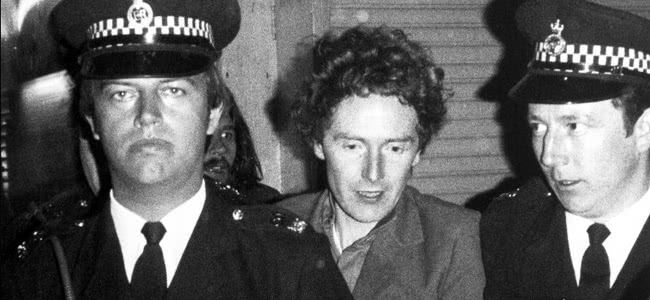

Malcolm McLaren

“It’s best to go into an artist management relationship knowing a bit about what it is that you’re tying to do, then look for someone that might fit that,” offers Hunt. The seemingly madcap ideas of Malcolm McLaren is a good example. McLaren’s management of the Sex Pistols and The New York Dolls perfectly suited his own publicity stunt schemes and attempts to boost profile through controversy. And it worked a treat.Case in point: McLaren was the brains who organised the Sex Pistols’ infamous ‘God Save The Queen’ performance on the River Thames. He was arrested while the band instantly dominated news coverage around the nation.

The symbiotic relationship between McLaren and his ferocious punk firebrands was they were both looking for someone who ‘spoke their language. Or as Hunt puts it, good artist managers are people who have “an enthusiasm or passion for what [they] do and someone that wants to make things happen; that can hear that there is a market [and] is willing to take a few negative answers in order to find it.”

Want to learn how to be an artist management? The Australian Institute of Music offer courses in Entertainment & Arts Management, where you’ll get all the skills you need. Apply now.