How many times have you posted or shared a photo on social media that wasn’t yours? Perhaps it was of a nice sunset, or an inspirational quote. Maybe you were even in the photo, but it was taken by someone else. In all of these instances you would not own copyright to the image and, if it were re-posted without proper credit or payment, it could get you in a lot of trouble. At times, crediting a photographer may not even be enough to bypass copyright infringement.

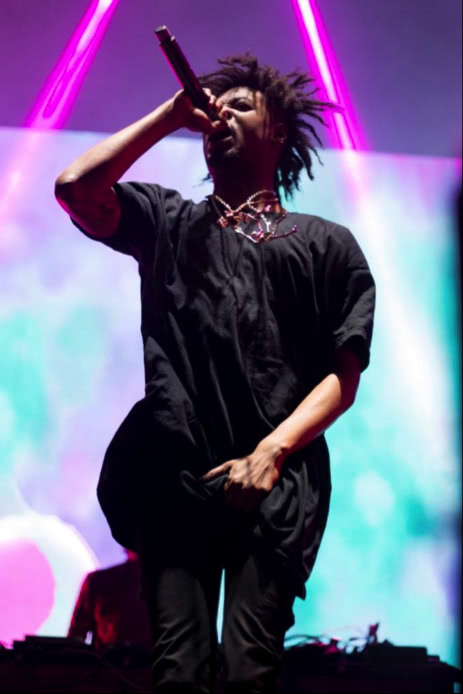

Header image: Danny Brown at Beyond the Valley 2014 by Brandon John

Copyright laws are becoming increasingly important to enforce, as technology is making it easier than ever to reproduce someone else’s work. You might have infringed copyright laws without even knowing, and it can not only have legal implications, but also undermine a photographer’s job and the work they produce. I promise not to bore you with an in-depth factual account of the technicalities of copyright (although it does need to be mentioned at some point), but instead provide you with a guide to posting photos on social media and a reminder of the severe consequences of stealing intellectual property.

Melbourne photographer Michelle Grace Hunder recently had one of her images of Danny Brown posted by the US rapper himself, to an audience of 349 thousand Twitter followers.

An exciting moment for Michelle, right? Well, it should have been. Instead, Michelle was robbed of her euphoric moment and ownership of her image. Danny shared the photo without crediting her, meaning Michelle had no idea that her work had been stolen until Twitter users made her aware of the post. Luckily, Michelle is a well-known music photographer, so others were able to recognise her work immediately.

The image was receiving a great deal of exposure, but it all went to waste as none of that exposure was given to Michelle. Apart from a handful of her followers, no one knew who took the image.

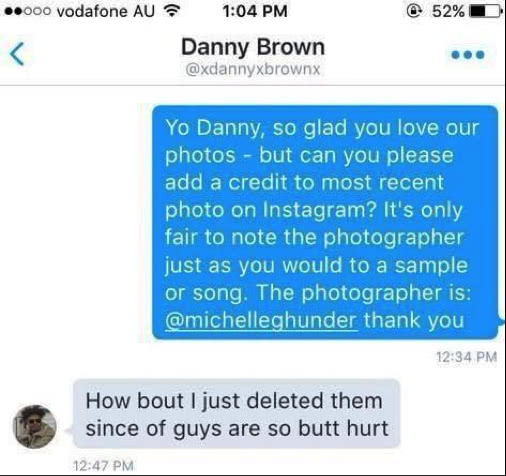

Dealing with this on a weekly basis for over five years, Michelle was fed up with her work being stolen and took a stand. Lauren Ziegler, editor of Howl & Echoes (the publication Michelle shot that image for), engaged with Danny Brown via Twitter, asking for the image to be properly credited – not demanding compensation, simply requesting that Michelle’s name to be placed alongside her own work.

What happened next was something Michelle – a huge fan of Danny’s – had never experienced before. Rather than simply adding a tag to the post and apologising, Brown began a fiery (and allegedly alcohol-fuelled) Twitter rant.

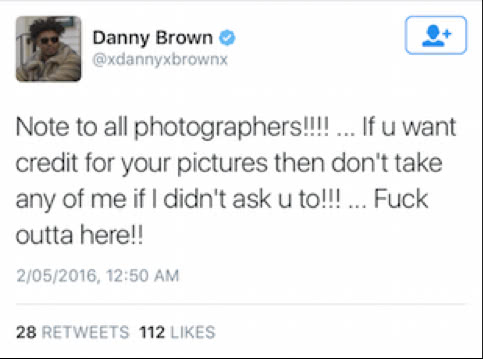

Danny Brown, who was in the country touring with regional festival Groovin’ the Moo, then deleted Michelle’s photo and followed with a series of harsh tweets, including the one below:

The point that Danny makes in this particular tweet is invalid, as artists’ PR and management teams approve photographers to shoot their shows. If an artist doesn’t wish to be photographed, PR and management will simply not allow photographers. This means that while it may have been indirect, Danny ultimately did ask photographers to shoot him.

“Usually they ignore you before they abuse you,” Michelle laughs in disbelief as she retells the incident.

“This isn’t the first time Danny has posted one of my photos without crediting,” she adds.

But it’s the photographers job. Haven’t they already been paid for their work?

“[Music Photographers] aren’t in it for the money,” Michelle says. Very few get paid for what they do, and she explains that this is due to a variety of reasons, the competitive nature of the industry being chief among them. Michelle is one of the very few who does get paid, but sometimes still shoots for free when working for a publication.

“When I’m not shooting for an artist directly, but still want to document the show for my own personal reasons, then I’ll shoot for a publication,” she explains.

This is exactly what happened for Danny’s Melbourne show, meaning that Michelle was not paid. She admits this is rare for her, but that it’s the norm for the majority of music photographers.

Imagine yourself working for free. Putting hours of effort into your work, only to have it stolen from you, shared or reproduced with your name nowhere to be seen. This is the harsh reality many photographers are facing in a time where people believe that anything found on the internet is theirs to take and use however they please.

“It’s also a massive slap in the face when you see a photo of yours with 400,000 likes and nobody knows who took that photo. That’s one of the most frustrating things ever, and it’s happened to me so many times I’ve lost count.”

As a music photographer myself, this is an issue I also face. Combining my love of music and photography, I volunteer my time to photograph bands. It’s what I’m passionate about, but it’s incredibly disheartening when an image I’ve taken has been shared and I haven’t been acknowledged.

I saved for months to buy my own basic camera gear and pay a monthly bill for photo editing software, but I have never been paid a cent to shoot live music. I knew to expect that starting out, that’s not the problem; it’s that people don’t even have the decency to tag you alongside a photo you took. It makes all the effort I put into shooting and editing suddenly seem worthless. How can people appreciate your work if they don’t even know it’s yours? People need to consider the costs photographers pay before they steal their photos without a second thought.

As Michelle says, “You’re told when you start [music photography] that the most flattering thing that can happen is to have your photo shared.”

“It is really flattering when a huge artist shares and appreciates your work – that’s the biggest compliment that you can get – but it’s also a massive slap in the face when you see a photo of yours with 400,000 likes and nobody knows who took that photo. That’s one of the most frustrating things ever, and it’s happened to me so many times I’ve lost count.”

“Tags mean everything,” Michelle says. “It’s how I’ve built my business, so for someone to say that a tag doesn’t mean anything or that it doesn’t have a quantifiable economic value is really wrong”.

In a survey of 50 music photographers around Australia, 90% answered ‘yes’ or ‘sometimes’ to working for free, while 88% answered that they’ve had at least one of their images posted on social media without permission or credit.

You may be thinking that a simple solution to this would be to add a watermark (usually a logo or name) to the image. However, Michelle advises against this.

“There’s no professional I know who uses watermarks. They look ugly, and even if they are used, they end up just being cropped out. The other alternative is that people just won’t use the photo.”

“It’s actually not even the point; you’re asking someone to do something to prevent the theft of their work. Let’s actually educate people instead, rather than saying, ‘Oh, I’ll just put a watermark on it and it’s going to solve everything’ – because it doesn’t.”

Sydney-based musician Montaigne aka Jessica Cerro reflected on the issue from a historical point of view, saying that “a painter’s watermark was their signature, written onto the work of art. The artist continued to get work if they were good because it was easy to find the source of the creation.”

“Nowadays, you can still have a watermark on things you do, but because our personality on the Internet is often indolent, we can rarely be bothered to pursue a watermark if there is no direct link provided that takes us to the artist’s page.”

Montaigne is one of the many artists who used the Danny Brown incident as an opportunity to educate their followers on why crediting is important for photographers.

“If you take the 15 seconds needed to credit the artist, you support the artist. You support the creative field, which means that it survives and thrives, and its survival is in your interest.”

“The arts suffer because of the popular notion that strangely only people who are not artists hold: art should only ever be free because it is done out of love and primal need. That is a very romantic notion, but sadly, it is not realistic.”

Michelle agreed that sometimes people don’t credit photographers due to laziness, but believes that most of the time it comes from a lack of understanding.

Where do the copyright laws come into this?

If you’re a user of social media – specifically Instagram, Facebook or Twitter – you would have had to select that you agree to their Terms of Use and Community Guidelines upon signing up to the websites/applications.

Here are the main points relating to Copyright in Facebook and Instagram’s Terms of Use:

Twitter’s User Agreement states that “Twitter respects the intellectual property rights of others and expects users of the Services to do the same.”

“A lot of people go, ‘Oh, it’s on the Internet, so you can steal it’. Well actually no, you can’t, and all of those platforms that we’re sharing on are really aware of our laws, and will remove something that’s already copyright protected,” Michelle says.

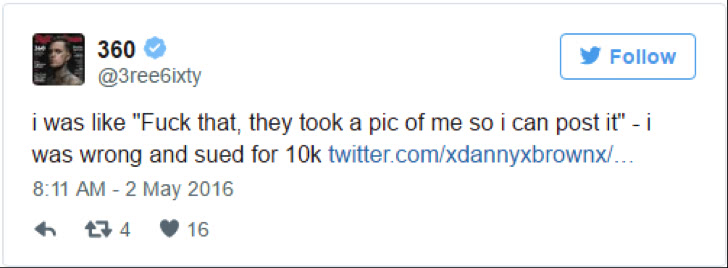

If you don’t follow these rules (which are made in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968) you may end up having to pay a hefty fine or, in extreme cases, even face jail time. Australian rapper 360 aka Matt Colwell admitted via Twitter that he had been sued for $10,000 due to not understanding copyright laws as they relate to photography.

According to Michelle, who is also “a good friend of Sixty’s”, the photo was a shot of lightning which he shared on Facebook, rather than anything music-related.

“Photographers outside music are brutal – they know their rights, and they’re not used to their work being stolen like we are.”

How do we fix this?

There are various resources available that explain in simple terms what copyright law is, and how to avoid infringing copyright, which is becoming increasingly important with the sharing tools that social media is providing. The Australian Copyright Council is a valuable resource for understanding copyright, as the information provided is based on the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), which sets out copyright law in Australia. Outlined in their ‘Introduction to Copyright in Australia’ fact sheet are some key points:

- Copyright provides creators with an incentive to create new works and a legal framework for the control of their creations.

- Copyright protection is free and applies automatically when material is created.

- There is no registration system for copyright in Australia.

Michelle suggested that copyright laws concerning photography should be enforced in school.

“Everybody knows you can’t plagiarise – you have to credit your source. It’s exactly the same [with photography], so why isn’t that really being drilled home through schools?”

“Everything is so visual now, so photography is very important, yet the value of our art has reduced so much,” she adds.

Expanding on her solution, Michelle says that photography theft should be enforced just as strictly as plagiarism.

“You can get in so much trouble. You can get kicked out of uni – people know how serious that is. There just needs to be a similar kind of respect given to the artists who are creating those images that are being used.”

The more that photographers speak out about the troubles they deal with on a regular basis, the more exposure this issue will receive. Hopefully this can lead to a world more educated on the proper use of images, which is absolutely necessary in a digital age.

If you see a photo posted and it’s obvious that the person who shared it wasn’t the creator, ask them who took the image. As Michelle says, “Just because you’re in a photo, it doesn’t mean you have any rights to it”. Educate yourself, and help to stop the theft of intellectual property. Before posting your next photo on social media, think of the consequences it could have – especially if you aren’t the owner of the image.